Automated Districting that Preserves "Communities of Interest"

The 2016 election saw unprecedented foreign interference in American elections. These affronts — whether by misinformation or outright hacking — have by no means abided. Unfortunately, 2020 witnessed domestic attacks on free elections and democratic principles that are bolder and in many respects even more insidious. The strategems are legion: facetious voter ID laws, strategically under-resourced polls, disenfranchisement of huge swaths of the electorate, and of course the partisan perversion of legislative districts: gerrymandering.

In June 2019, the Supreme Court definitively dropped the reins on partisan gerrymandering of Federal districts. Congress has the Constitutional authority – and responsibility – to do away with partisan districting. It must be forced to do so. One strategy for this would be to mandate automated districting. Here’s how it would work.

At 2018 meeting of the American Association of Geographers, Eric Holder gave a speech on the fight against gerrymandering he’s leading with Arnold Schwarzenegger. Before he escaped at the end, I asked him what factors he would ideally want considered in statewide plans. His answer: equipopulous, contiguous, compact districts, whose boundaries respected existing political subdivisions and communities of interest.

I had just written a paper, documenting strategies for generating statewide maps that respected equipopulation and contiguity while optimizing for spatial compactness. In new work, I show how that project can be extended to target the Attorney General’s final objective, deference for existing communities. The approach is straightforward. One simply manipulates the areas or perimeters of the geography to elevate existing jurisdictional boundaries into physical space. For example, if the “political subdivisions” you care about are counties, you’d just shrink each county towards its center – try adjusting the slider:

If you then generated “spatially compact” districts, where constituents lived close to one another, the computer will tend to avoid the empty spaces that you’ve created, gaping between the counties. This strategy provides a sliding scale between physical compactness and preserving communities: the more you shrink the communities, the more they will tend to be assigned to the same Congressional district. You can see this visually below or, more formally, in this working paper.

This strategy is very general. If you care about townships in addition to counties, you can successively shrink the townships and then the counties that contain them. This works for any set of hierarchically “nested” geographies. Above, I described compactness as the distance between people. Another common approach is to consider the ratios of areas to the squares of the perimeters; this rewards maps with short and direct boundaries. To apply the “scaling” method, one would simply rescale the perimeters according to how “bad” it would be to cut them. For example, a meandering river might make for a long perimeter while separating two communities that are in fact culturally or economically separate. Culturally, that might be an optimal boundary. If so, one could rescale that length of the perimeter to “encourage” an automated optimization to follow that path, despite its physical length. It’s worth acknowledging that this method works less well for “communities of interest” that are not initially contiguous or compact. Physical scaling doesn’t isolate them from their neighbors. In important ways, these manipulation of physical geographies to reflect nonphysical attributes is related to cartograms.

In short, this method completes the “suite” of methods needed for traditional districting principles: equipopulation, contiguity, compactness, and a respect for existing communities. These methods aren’t perfect but they’re very good and they could be further refined. They offer nonpartisan statewide maps, optimized for the objectives we claim to care about. In 1972, then-Governor Ronald Reagan opined that “there is only one way to do reapportionment — feed into the computer all of the factors except political registration.” Today, the computer can do it. Can we?

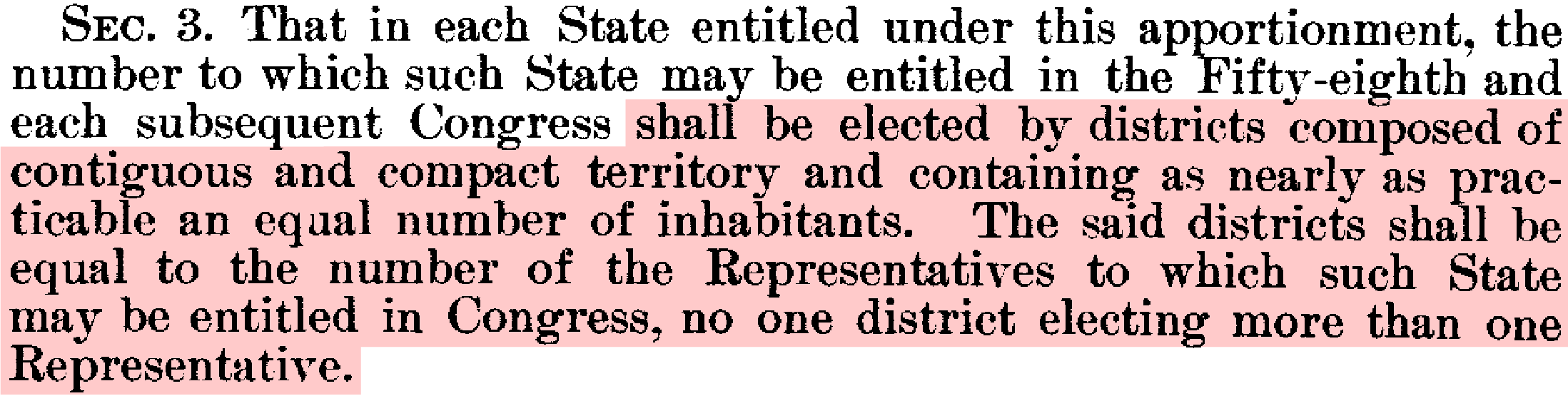

Congress has total control over the districting process. Article 1, Section 4 of the Constitution gives it the power to simply do away with partisan districting, and send the process to the computer. To pass this bill, a clear proposal is needed that normal people can understand. Here is what the districting requirements looked like back in 1901, when Congress was using its Article 1, Section 4 powers:

Readable! These are great requirements, but the word “compact” is ambiguous. There are many competing definitions, and while they all have similar basic intent and effect, one should be chosen. More-precise language would be: “The districts shall be defined to minimize the distance between co-constituents.” If you also care about split counties you could add, “after scaling counties by a factor of 2/3.”

Republicans control a majority of state legislatures, and they have used this power to entrench their majorities in state Congressional delegations. So long as their control continues, they will not voluntarily relinquish the power. To enact non-partisan districts nationwide in 2022, Democrats will need the bill to pass both the House and the Senate. To do this, they needed all four toss-ups votes in the Senate — North Carolina, Colorado, Arizona, and Maine — as well as the tie-breaking Vice-President. They didn’t get this, and they are unlikely to win both seats in Georgia. But every Senator should be forced to take a stand for or against fair districts. Candidates for office who will not commit to democratic principles simply cannot hold the public trust. The best way to do this is with specific, straightforward, debatable language that voters can understand. The Democrats’ Fair Districts Pledge does not achieve that. There is no precise, proposed solution. For that reason, it does not bind the Democrats themselves to a policy that voters can evaluate and hold them to.

The Supreme Court has thrown responsibility for fair districts squarely in the lap of Congress, where the founders intended it to lie. Tools for computionally-automated districting are sophisticated enough to allow for meaningful, reasoned debate over the values that we express through maps. Now more than ever, Americans must demand that their representatives enshrine their highest values in the Democratic process.